Moroccan Innovation

Morocco is a land that has mystified and enchanted travelers for ages. Situated between the Mediterranean Sea, the Atlas Mountains, and the Sahara Desert, Morocco is a place of geographic and cultural diversity, situated at the confluence of civilizations. Morocco has absorbed the influence of the native Berber and other North African tribes, Arabs from the East, and French and Spanish cultures from across the Mediterranean.

Morocco is the destination of the huge Saharan caravans of lore, with hundreds of camels traversing vast expanses of desert to bring trading goods from as far away as Timbuktu in Mali towards the sea. Even the names of the key Moroccan cities evoke a sense of wonder and excitement: Casablanca, Marrakesh, Ouarzazate, and Fez.

This agglomeration of Moroccan cultures and geography makes for an interesting locale in which to study innovation.

There are numerous attributes of Morocco that warrant investigation in terms of examining how ancient and modern inhabitants of this land were able to innovate to solve various problems they faced as they sought to develop and extend their civilization in the face of natural and man-made obstacles to survival.

In addition to survival, these innovations include efforts by the inhabitants of Morocco to make their lives more bearable in the harsh climate of some parts of their country. Many of these innovative solutions can still be seen today, and I have chronicled them in the sections below based on information I gathered from a recent trip to Morocco.

Moroccan Desert Climate

Build with the End in Mind

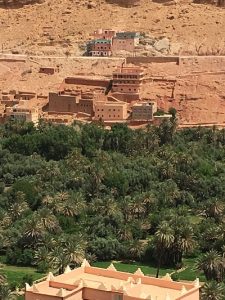

In an extremely dry climate such as one finds in much of Morocco, the predominant construction mechanism for centuries has been the mud brick and mud wall. A mud brick is made using the soil from the area which, combined with straw, other organic materials, and water, can be cured in the sun to form a hard, reddish-colored building material. Mud wall construction techniques involve pouring mud into form boards and packing the substance down manually to form a strong building material. One of the best examples of mud-based construction is the famous fortress of Ait Ben Haddou, located near the modern town of Ouarzazate, on the caravan route between the Sahara Desert and Marrakesh (known as the route of a thousand Casbahs (castles)). Mud brick would not be a suitable construction material for a wet climate, but it works well in the very arid portions of Morocco.

Building Constructed of Mud Walls

Ancient Mud Wall Construction Technique

Modern Mud Wall Worker

What is particularly interesting about the design of Ait Ben Haddou and many of the other mud-brick casbahs of the region is the appearance of numerous square holes in the sides of the walls of these buildings. The holes are about four inches wide and were the location where the builders of the walls inserted long wooden posts horizontally to serve as scaffolding to support workers who were assembling the structure. Since timber was scarce in a desert climate (the trees had to be obtained far away in the more forested Atlas Mountains), the builders could not afford to leave the posts in place. Moreover, they would have given enemies a means of climbing up the walls. Instead, the designers of the casbahs removed the posts and left the openings intact, which, in turn, served a secondary purpose.

In the desert climate, the mud walls needed the ability to handle intense heat and to shed any water that seeped its way into the relatively porous mud bricks. These holes, when properly positioned in the structure, allowed the walls to breathe in the intense heat by circulating air throughout the structure while also shedding water in the rare event of a rainstorm.

Mud Wall Hole – Detailed View

Mud Wall with Construction Holes

Innovation Lesson – The builders of the mud edifices in Morocco found a way to add a step to their construction process that ended up benefiting the overall structure later in its life. We often think of the process of building something as a temporary process, and we do not usually integrate the two processes (construction and eventual occupancy) in a way where there are specific ties between the two. In other words, we see construction as a phase that we have to get through in order to occupy a structure, and we think about construction as a temporary step.

The lesson here for innovators is to think about steps early in the process of creating something new where those initial steps become foundations for long-term success of a project. Scaffolding components that are needed to build a building may not always need to be temporary, especially if some element of the building process can be leveraged to improve the long-term viability of the structure.

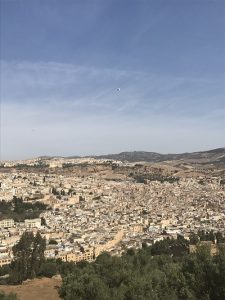

Complexity can Benefit a Design

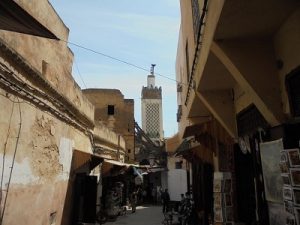

A word one hears often in Morocco is medina, which is Arabic for the old town or city center. Many Moroccan cities have well-preserved medinas that continue to be inhabited today, of which the best-known example is that of Fez. A characteristic of the Moroccan medinas is the chaotic design of these areas. When we think of a city, we often think of sweeping boulevards or grid networks of interconnected streets with a logical, often symmetrical layout. The Moroccan medinas are the exact opposite of that model. A medina is a maze of tight alleyways, illogical dead-ends, strange angles and turns, and two-story buildings on both sides of the street that prevent a person walking through the streets from being able to see anything in the distance to provide bearings and direction.

Fez Medina Overview

Walking through the Fez medina is an adventure even for the modern traveler equipped with GPS location finding and digital mapping. It can be disorienting and confusing, even with (limited) street signs posted on some of the walls. Add in fast-moving crowds, donkeys carrying goods, moto-scooters, loud noises from artisans’ shops, smells emanating from restaurants, and shopkeepers with goods spilling out onto the streets, and even the savvy traveler can become lost in a medina.

The question thus arises as to why a city would ever be designed in this manner. After all, many ancient civilizations had logical layouts to their streets, such as the four intersecting routes (the East-West orientation of the decumanus) and common elements found in almost every Roman city (coliseum, theater, temple, forum, etc.).

Medina Dead End Street

One reason why medinas are so chaotic is that the design itself served as a defensive mechanism. In a relatively insecure area, a city would typically be protected by walls and gates. Indeed, some of the cities in Morocco were surrounded by several layers of outer walls. Yet history shows that even the highest and strongest gates can be breached, so the medina is designed in a way where once the attackers gain entry into the city, the defenders would still have an advantage against the them because only the inhabitants of the city would know the maze of streets.

In other words, once the breach in the walls occurred, the attackers would have trouble maintaining the discipline of their forces in terms of advancing towards an objective given the tight, twisting, and turning streets. Moreover, the inability to see more than a few feet in any direction would hamper communication among attacking troops. Although this erratic design does indeed benefit the defender of the city, it should be noted that there is some sense of order in the medina. As Corinne Verner writes in The Villas & Riads of Morocco, “[t]he first impression of anarchy is nothing more than an illusion […for t]he medina is arranged in different sectors, separating the economic life of the city from the private life of its residents.â€

Fez Medina

Innovation Lesson – The medina design introduces complexity to enhance its overall security. As innovators, we typically strive for simplicity and avoid complexity at all costs, especially in terms of our pursuit of efficiency in operations. The question for the innovator thus becomes whether complexity might be of value in a process or technology for certain scenarios.

A great example would be a computer firewall. Although we typically focus our efforts on making strong firewalls to prevent intrusions into our systems, we do not spend a lot of time thinking about what the system looks like once the hacker is able to gain illicit entry into the environment. Sensitive data is almost always encrypted, but it is also typically in the same place, as we focus on maximizing the performance of database queries and simplified internal design. In an environment that requires extreme protection, perhaps the lesson of the medina is that even if an intruder gets past the firewall, confusion should be a tool one leverages to continue the battle to protect sensitive information.

Provide Shared Value

One of the most striking things one encounters in the various medinas in Morocco is the public fountain. As one walks through the labyrinth of the medina, with its dark and sometimes dirty streets, all of the sudden one will stumble upon an elaborately decorated fountain. The fountain is typically 8-10 feet tall and 6 feet wide and consists of zellij tiles covering its walls and basins, along with brass spigots for dispensing water. Zellij tiles are brightly colored, geometrically-shaped pieces of fired terracotta (clay) that are glazed and chiseled by local craftsmen. A fountain might also have a green tiled roof overhang, to create a semi-private space for the person seeking replenishment.

The fountains are usually designed to provide water both for people and for animals, and in a desert climate such as that found in many Moroccan cities, the fountain is a life-sustaining entity. These fountains were not public works projects managed by the government. Rather, they were the result of gifts from wealthy patrons in the city who sought to fulfill the Koranic requirement to engage in acts of piety and donations to the poor. The wealthy residents of the city would sometimes endow the fountains with plaques documenting their beneficence.

As Achva Benzinberg Stein of the University of California at Berkeley notes in Morocco: Courtyards and Gardens, “[t]he fountains of Fez are miniature public oases in the city,†and the Arabic word for fountain (seqqaya) is related to the Farsi word meaning “to give drink.â€

Public Fountain – Fez

Fountains have been ubiquitous in Fez in the past, and Stein writes that at one point in 1550, the author Leo Africanus counted nearly 600 fountains in the city. Water is an extremely valuable commodity in the desert, and its role in sustaining life for people and animals, in cleansing and protecting from disease, and in purifying before prayer sanctifies the location of the fountain. For the wealthy donor who builds the fountain and gives it to his city, the benefits are an improved overall environment in which to live. If the fountain is near the home of the wealthy person, then people and animals delivering goods to the home would benefit from being able to drink nearby. If it is near a shop owned by the wealthy person, then customers would be more likely to spend time in that area, thus helping the business. The fountain would thus enhance the overall quality of life in the community, which, in turn, benefits the wealthy person who lives in that community.

Public Fountain – Fez

Innovation Lesson – In business innovation in modern times, we usually are forced to focus our work on either reducing costs or increasing revenues. We either seek to find new efficiencies that help us reduce costs in operations, or we create new products and services that bring in new revenue. Since our innovation work is funded from company revenues, this is understandable. However, writing in the Harvard Business Review, the authors Michael Porter and Mark Kramer remind us that there is a third potential objective of innovation efforts: shared value.

Porter and Kramer define shared value as “generating economic value in a way that also produces value for society by addressing its challenges.â€Â In other words, they continue, “[a] shared value approach reconnects company success with social progress.â€Â The story of the fountains in Moroccan cities shows a centuries-old connection to this concept of shared value and can point the modern innovator in the direction of finding ways to deliver value to one’s community. Innovation can be focused on delivering social benefits which, in turn, provide commercial benefits in terms of helping the community overall.

Public Fountain – Fez

There is another lesson to be learned from the fountains – that of beauty and function. Unlike the utilitarian public fountains in the United States and elsewhere, the public fountains in Morocco are often amazingly beautiful. A wealthy patron could fulfill his Koranic injunction by simply installing a metal spigot and stone basin in a wall, thus meeting the basic needs of the community. Yet what we see in Morocco are elaborately ornamented fountains that are works of art in and of themselves.

Although some fountains have faded in their glory, many are still stunning in appearance even today. This serves as a reminder to the innovator that when designing something that is functional, it is not necessary to forgo beauty in the design. In other words, just because something is functional does not mean that it cannot be beautiful.

Indeed, the zellij tiles that one sees so often in Moroccan interiors often rise up to about the height of the shoulder of the average person. This is because, Stein observes, the tile served an additional function besides being decorative. The inhabitants of a dwelling did not want to brush up against plaster walls and discolor their clothing with the dust of the plaster. Thus in addition to being easy to maintain, the smooth, glazed tile from the floor to the shoulder helped keep clothing clean while also beautifying the space.

Do Not Let the Outside Define the Inside

Another characteristic of Moroccan architecture is the riad, or private home with a garden or courtyard. Located within the medinas, the riads are places where the wealthy would isolate themselves from the din and clatter of the busy streets. Indeed, many riads today have been converted into private hotels, and one of the most popular places to stay in a city like Marrakesh is a converted riad.

Zellij Tiles – Shoulder Height

When one approaches one of the many entrances to the medina in Marrakesh, one sees numerous hand luggage carts affixed with the logo of various riads that will be used to transport the luggage of visitors to the hotel, since cars cannot enter the medina.

Riad Luggage Carts

What is perhaps most interesting about riads is the contrast between their outer and inner appearances. Although some riad doors are made of elaborately-carved wood, for the most part the entry to a riad consists of a tall door and even taller walls, tucked away on some non-descript street corner in the medina.

One often stumbles across a riad unexpectedly, since there are not always large signs or grand entryways into these dwellings. Yet once one passes through the wooden door, one enters a world of tranquility and beauty, in stark contrast to the noise and chaos of the street outside. The entryway typically opens to a courtyard containing a fountain, with colorful zellij and the sound of flowing water filling the space. The multi-story courtyard is open to natural light and is surrounded by the rooms of the riad, with dining areas and sometimes even a pool on the top floor looking out over the rooftops of the city.

As Verner writes, “Moroccan homes are almost hermetically sealed and their facades are devoid of adornment […and o]nly some muted ornamentation on the street-side doors, designed to allow a laden donkey to pass through easily, hint at the refinement to be found within.â€

Riad Non-Descript Entry

Riad Interior Courtyard

Riad Rooftop Pool

Doorway to Courtyard

Innovation Lesson – When we think about great buildings and structures, we often think about their exteriors, with wide, sweeping entryways and gardens, tall columns, grand porches, and ostentatious facades. While the interior behind these entryways is often just as elaborate, we sometimes forget that in a typical residence, the place where one spends most of one’s time is on the inside. The designers of the riads were limited in what they could do on the outside because of the narrow alleyways of the medinas. Yet they probably also recognized that it made more sense to invest energy in beautifying the interior because that is the place where the occupants would be spending most of their time.

For the innovator, the lesson here could be that one should invest more time working on innovative features and designs for those portions of an entity where the user will spend the majority of his or her time rather than on the upfront portion of the entity. In terms of a software application, this would mean thinking less about the initial screens of an application and more about the working parts where users will spend the most time. We often hear that first impressions are of great importance, so we tend to focus on the upfront steps in a process or technology. Yet this should not come at the expense of the more intensively-used portions of a process or technology.

Repeated Patterns can be Innovative

A prominent design theme in Moroccan buildings is the use of zellij tile on the floors and walls. Zellij tiles are made from local clay which is fired into small squares about 4 x 4 inches, with a thickness of about one-fourth of an inch. The tile is then glazed with one of seven colors and cut into smaller pieces in various shapes to be used in decoration. Stein notes that traditional Moroccan zellij used turquoise and white colors, but over time the palette expanded to include seven colors: “three basic (white, black, and sandlewood brown) and four complementary colors (red, green, yellow, and blue).â€Â Stein writes that this set of seven colors appears “throughout the Islamic world and is based on the sacred associations of the numbers three, four, and seven.â€

In addition to tile, Moroccan interiors also use plaster for walls and carved-out decorative elements in the hardened surface. There is a repeated combination of elements evident in the tile and plaster in Moroccan design: geometric, floral, and epigraphic (script). As one goes from one building to another, whether the structure is a riad, medersa (Islamic school), a tomb, or a mosque, one sees frequent use of these three design elements along with the seven colors in various combinations.

Zellij Tiles – Detail

Geometric shapes are triangles, polygons, stars, squares, and other mathematically-familiar designs, with small pieces of tile combined in elaborate detail to result in larger patterns. Designers tend to favor smaller, more intricate geometric pieces woven into designs with astronomical or religious significance. Floral shapes are more natural looking, shaped like plants and flowers. As Stein notes, “[for floral patterns, o]ne of the principal motifs is the touriq, a botanical ornamentation composed of interlacing floral, foliage, and palmette patterns.â€Â The palmette leaf appears frequently, reflecting the importance of the date palm tree, which grows in abundance in various locations in Morocco.  Dates are an important source of nourishment for Moroccans, and they are prized as a sweet used to break the all-day fast during Ramadan.

Zellij Tiles and Geps Plaster Carvings

Script is Koranic verse in Arabic, carved into plaster or painted on tiles in flowing characters. Stein observes that “[i]n the epigraphic patterns, the cursive form appears most frequently [but w]hen sculpted in stone […] the Kufic style, a monumental script par excellence, is preferred.â€

The script is usually carved into plaster as part of a process known as geps (derived from the Greek word Gypsum, meaning the rock base of the plaster). Geps, featured prominently at the Alhambra site in Granada, Spain, is carved onsite by artisans following a stencil of the Arabic script for the decoration. Geps appears fragile because of the delicate appearance of the carved plaster shapes, but it can survive a long time, with some geps dating from the 12th century still intact in Morocco today. As one enters a new building, these three elements (geometric, floral, and script) along with the seven colors appear as familiar friends, yet each dwelling has its own aura and sense of place, despite leveraging these common design themes.

Zellij Tiles at Saadian Tombs in Marrakesh

Innovation Lesson – When we think of innovation, we think of things that are completely new or novel. In other words, the very essence of the word “innovative†itself focuses on things that are new, or never before seen. The repeated patterns in Moroccan architecture remind us that innovative does not need to always be “brand new.â€Â Despite the shared components of these three elements and seven colors, each building in Morocco has its own sense of novelty and creativity. The spaces decorated by the geometric, floral, and script elements and seven colors feel alive and new, as each designer uses the elements in different manners to arrive at his or her final design.

Each time I entered a Moroccan edifice for the first time, I looked for the repeating patterns and colors and was amazed at how the designers could create something that is at once uniform and yet is also unique at the same time. For the innovator, this can serve as a lesson that building something novel can be accomplished using repeatable patterns and common design elements.

Zellij Tiles, Geps, and Wood Ceiling

Rather than struggling to find a brand-new approach to solving a problem, an innovator could make a small modification to a previous approach to solving that problem to see if he or she could generate new results.

Innovators often shy away from using repeatable or consistent patterns, wary of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s dictum that “[a] foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines.â€Â Yet in the case of Moroccan design, the consistency of these three elements and seven colors results in an experience in every building that is arguably more transcendent than would be the case if every building tried to be dramatically different.

The zellij tiles are more than just decoration. As Stein notes, “[t]his multidimensional art form has deep religious meaning expressed through its geometries and the mathematic and astrological significance the figures carry […and t]he hypnotic, repetitive designs are used to foster a meditative and religious connection to the Divine.â€Â Repeated patterns appear in architecture dating from Roman times to the present as well.

According to one critic, the great American architect Louis Kahn “never gave up on his fascination with ancient Roman architecture and lessons learned from his classical Beaux Arts training in the 1920s about the visual power of the strong axis, load bearing structures and the fundamental resonances of the circle, square and triangle.â€

Think About Human and Natural Design Elements

Although there are places in Morocco with enough snow in winter to permit alpine skiing, the country is for the most part a dry, desert climate in its inland cities (such as Marrakech). The desert presents many challenges to an architect in terms of extreme heat and sunlight during the daytime, along with the potential for extreme cold at night. The architect in Morocco confronts the challenge of living in such an intemperate climate at two levels. First, he or she leverages the natural processes of heating and cooling to improve the livability of a structure.  Second, he or she leverages the way humans react to a structure to increase its livability as well.

In terms of nature, the Moroccan structures are designed to ensure airflow in the summer (taking advantage of prevailing winds in the desert) while providing for warmth at night to fight against the cooldown that occurs in the desert after sunset. Stein writes that “[l]ow, wide courtyards […] capture cooling breezes, while taller buildings provide more shade and shelter from the hot sun.â€Â Patio areas, she continues, possess shaded areas and cool tile flooring to counter the heat of the day, while later in the evening the stone of the building radiates back the heat it gathered during the day to keep the residence warm.

During the day, the shade and shelter provided by overhanging roofs is preferred by residents. At night, Stein concludes, the heat captured from the sun during the day is radiated out through floor tiles and the courtyard is transformed into a pleasant place to stroll. Moroccan edifices also typically have thick walls and high ceilings, which allows rising hot air to escape through small holes at the top of exterior walls. Patio doors allow air and light from the courtyard into the house.

Interestingly, Stein notes, Moroccan homes are typically designed around maximizing summer cooling rather than winter heating, and one often finds the interior rooms to be rather cold in the winter. In my travels around Morocco in the warm month of May, I was struck by how often I would enter an ancient Moroccan structure and find that it was much cooler than the climate outside, even without modern air conditioning.

Courtyard Garden – Marrakesh

A second design attribute focuses not on nature but on the human experience. When one enters the interior of a Moroccan courtyard, one is struck by two sensations: colors and water. The zellij tile provide vibrant colors on the walls (and sometimes floors), and floors are also sometimes colored  or white marble.

Stein observes that “[b]rightly colored tile decorations can simulate the sensory experience of a garden without the water needed to maintain living flowers and shrubs.†Outside the home in the medina and the outskirts of town, Morocco can be a monotone palette of reddish brown due to the dry climate and prevalence of red clay in the exterior building materials. By contrast, according to Stein, the Moroccan architect designs the colors in the house to ensure a “contrast with the monochromatic landscape and provide a simple and effective means of creating the illusion of lushness and keeping the desert at bay.â€

Courtyard Fountain – Marrakesh

One sees a lot of green in the courtyards, including the roofs of the galleries which are often covered in green tiles, thus creating what Stein calls “an abstract substitute for plants.â€Â In courtyards where the builder integrates actual plants into the design, she continues, the focus is on “[l]ong axial paths, often lined with tall evergreen trees, [that] draw the eye into the distance, while green blocks of vegetation make a dark corridor to entice the visitor.â€Â Stein writes that the designers even leverage a trompe de l’oeil (trick of the eye) by placing flower and vegetable plants below the level of the footpaths, which serves the dual purpose of providing shade for the plant roots while giving the human occupant the impression of “walking on a colorful, fragrant Persian carpet.â€

Courtyard Garden

In addition to visually stimulating the human occupant of a property by colorful design elements, the Moroccan architect also incorporates the precious resource of water into the design. Water is a scarce resource in the desert, and designers are careful to incorporate it in low-flow and modest, but nevertheless enticing, forms.

Typically, the designers will locate a fountain at the center of a courtyard in a basin and will ensure that a small flow of water spills over the edge of the basin into an overflow area to be reused. Verner reminds us that “[t]he paradise of Islam is […often] portrayed as a perpetually gushing fountain.â€Â Articulating the same concept, Stein notes that this is a “symbolic expression of plenty†and the basins are often built “in the shape of an octagon, symbolic of the eightfold nature of Islamic paradise.â€Â The sounds made by the flowing water, she writes, “reinforce the feeling of calm and the illusion of plenty in this hot, dry climate.â€Â She observes that water can either be rippling, to add a sense of motion to the static environment of the courtyard, or it may be “dark and quiet, a meditation on the infinite nature of the Almighty.â€

Innovation Lesson – Moroccan interior design is a classic case of form following function, which is a key element in modern innovation. For the innovation practitioner, the lesson here is a reminder that it is not sufficient simply to design a structure that is beautiful, nor is it sufficient to design one that is merely functional. Form and function can be combined in ways that significantly enhance the human experience.

Another lesson for the innovator is the reminder to take human perception into consideration when working on the design for a new solution. The Moroccan designers wanted to give the human the impression of being in a colorful garden with abundant water, even though the reality of their desert environment was limited flora and very limited water. Perception, it is often said, is reality, and innovators should leverage this notion to achieve creative new solutions.

If an innovator has limited resources available for a project, then he or she can leverage these types of techniques to improve the way that people experience the innovation. In other words, where resources constrain one’s ability to provide a complete experience, leverage the human power of imagination to render those elements that cannot be physically created.

Build to Last

One of the most striking attributes of ancient civilizations is the ability of something built hundreds or thousands of years ago to survive in good shape in the present day. As Verner observes, one Moroccan technique that resulted in a long-lasting method of construction is the tadelact technique of finishing plaster, which is used for the surface of fountains, pools, and walls. Tadelact is a finish that is applied to masonry surfaces at the end of the construction process in which the tadelact artisan spreads limewater over the masonry surface then allows it to dry.

The artisan then very slowly rubs the surface in a circular motion using a hard stone that becomes polished over time. The process of circular rubbing takes an incredibly long amount of time, with the tadelact finishing process progressing at a rate of about one square yard per day. Once completed, the surface becomes enamel-like and is impervious to water, thus its use for fountains and pools. In Marrakesh, the pools of the 12th century Menara Gardens use this technique and survive intact today.

Tadelact Fountain

Innovation Lesson – In our contemporary society we rarely have the patience to focus on things that last longer than a few years. Innovation is seen as meaning that we move forward constantly, rejecting and removing the old so we can focus on the new. This example of something that is built to last reminds the innovator that innovation is not just about short-term usage and disposal.

Rather, innovators can stake a claim by building things that leverage techniques that last for centuries. In the case of tadelact, the practice had fallen into disuse in Morocco but has recently seen a revival in Marrakech due to its beauty and longevity. The innovation lesson here is that sometimes a simple process, repeated over and over, can expand to become a great innovation that lasts for centuries.

Follow the Flow

One of the most stunning visual experiences in Morocco are the seas of date palm trees that seem to appear out of nowhere in desert regions. The stark contrast between the reddish tint of the soil, mountains, and surrounding buildings, and the intense green fronds of the tall date palm trees, is an amazing sight. The date palms resemble an inland sea as they follow the course of underground aquifers for miles and miles in various parts of the central region of Morocco. Some of these are fed by small spring sources that form rivers then divert underground to support the date palm trees.

Sea of Date Palms

A great example of one of these water sources for date palms is the Dades River, which carved out the Todra Gorge, a stunning rock canyon that is as narrow as 30 feet wide in some areas with 500-foot high cliffs on both sides. It is possible to walk through the Gorge to the source of the Dades river, which begins as a tiny spring that generates a constant stream of fresh water that travels through the gorge and into the aquifers supporting the date palms.

What is amazing is how this source of water, which seems so small that it could be covered by a few shovels full of dirt, becomes a massive underground river that supports the gigantic date palm farms that extend as far as the eye can see in many places. Interestingly, although they make intensive use of the water from the aquifers, the Moroccans have not attempted to dam this river or massively divert it for other purposes, trusting, rather, to the course of nature to allow the water to keep flowing to support the people in the area.

Todra Gorge

Water Source – Dades River

Stein notes that date palms are well-suited to the region, with a high tolerance for salinity in their water and the ability to survive in hot, sunny climates with proper irrigation. According to Moroccan folklore, the date palm “has to have its feet in the water and its head in fire.â€Â Date palms are also very useful as a bulwark against the encroaching sands of the desert.

Moroccans invented a process by which they take the dead palm fronds from the trees and lash them together into fences, which they then allow to be covered by advancing sands. The workers then build another palm frond fence on top of that one, and repeat the process several times until they form a sand dune about 15 feet high, which then can be planted with other brush to anchor the entire system in place, thus effectively stopping future migration of the sand in that area.

Innovation Lesson – There are three innovation lessons to be learned from the example of the Moroccan water sources and the date palm farms. First, it is surprising that this impossibly small source of water results in the support of massive agricultural businesses. Although it is common knowledge that even the mightiest rivers all start out as a small water source, actually seeing these sources can remind the innovator of the power of a single concept to drive amazing results. One goal of innovation is to find these small streams that can lead to mighty torrents, rather than expecting to find the torrent right away. Sometimes it is the smaller entity itself that is the source of the innovation.

A second lesson from this example is a reminder that while humans have the ability to make artificial modifications to nature, in some cases the most innovative solution is to let nature run its course and not overly-engineer the solution. Moroccans have harvested date palms in the region for thousands of years (they were originally brought to North Africa from the Indus River Valley), and rather than trying to grow other crops using diversions of the water in the region, the Moroccans have stuck to their traditional form of agriculture, using a crop that is well suited to the unique characteristics of their region, rather than another crop that might work well at first but not be sustainable in the long run.

A final lesson of the date palms is the importance of dual-use technology. In addition to being a great source of produce (up to six tons of fruit per acre), the dead fronds of date palms also provide the foundation for fencing that is critical for survival in a desert region, as high winds tend to blow the light-weight sands which can encroach on human dwellings if not protected by dunes. The date palms provide sustenance for the inhabitants as well as structural support for their fencing, and innovators should remember not to limit their focus to a single use as they come up with a new technology.

Date Palm Trees

Trust the Specialists

The need to manage water sourcing and distribution is a recurring theme in Morocco. Moroccans have been using systems of water basins, aquifer taps, and tunnels to distribute water dating back to the 12th century through structures called khettara. The first khettara in Morocco, built near Marrakesh, transported water a distance of 25 miles into the city. Stein writes that the “khettara comprise a series of shafts reaching down to an underground gravity-fed channel.â€Â Building a khettara, she continues, is a labor-intensive effort, as large amounts of soil must be removed to build the various elements of the system. In places where the water is transported across long stretches of flat terrain, one can still see above ground the remnants of the dirt removed for the tunnels.

Engineers form the dirt remnants into mounds with access shafts to enable future maintenance on the water tunnels, while the access shafts are built in a way to prevent rainwater runoff from reaching the fresh water below ground. Stein observes that “[t]he work of plotting the course of the channel is traditionally the domain of an expert.â€Â The exact location of a khettara, she continues, “depends entirely on field experience and the ability to distinguish subtle changes in vegetation that indicate the presence of water.â€Â Teams of artisans, she notes, travel from place to place working on khettara, following the demands of various communities as their water systems would need to be maintained based on falling water tables or storm damage.

Khettara Mounds Indicating Water Tunnels Underneath

Innovation Lesson – The concept of the specialist is sometimes a difficult one for the innovator to manage. The innovator is torn between leveraging the expertise of a person who knows a great deal about a process or technology and trying to move beyond the past ways of operating a process or technology.

For example, if an innovator is asked to redesign a process to improve its efficiency, the innovator will have to rely on people experienced in operating that process in order to learn more about how it functions today (the ‘as-is process’). Yet by relying on input from these experts, the innovator will necessarily receive information that is biased in support of the status quo, based on the way in which the process had always operated. Likewise, if the innovator ignores the status quo, then he or she might miss some key elements of the process that must remain in the future, re-engineered process (the ‘to-be process’). The lesson of the khettara is that specialists are critical to the success of a project even if one is trying to do something entirely new.

Khettara Water Wheel

Synthesize by Combining the Old and the New

Another specialist who put his thumbprint on Morocco was the French architect Theodore Cornut, hired by sultan Sidi Muhammad ben Abdellah in 1760 to build a seaside city from scratch at the intersection of maritime and Saharan trading routes. The result was the creation of the city of Essaouria, which is about 115 miles from Marrakesh via a relatively straight and level road heading towards the coast. The sultan envisioned the city to be a trading post for caravans so when they completed their treks from the desert interior they could trade goods with ships that would arrive on the Atlantic Coast. Cornut designed the city to be fortified from coastal attack (he was in the French Navy), but he also included Moroccan cultural touches found in the medinas in other cities. The result was a combination of the labyrinthine and narrow streets of some Moroccan medinas with broad, more ordered French city structure. As such, the old town of Essaouira is a gem in terms of its construction and has the unique ability to make a French citizen feel at home just as it would make a Moroccan feel at home. Walking in Essaouira’s medina, one moves from broad, open, straight roads to tight, narrow alleyways in short order, which is a unique experience in Morocco.

Essaouira Medina – French Style

Essaouira Medina – French Style

Essaouira Medina – Moroccan Style

Innovation Lesson – The lesson here for the modern innovator is a reminder of the power of combining old and new to develop a completely novel approach to solving a problem. The sultan could have hired a local architect to design his city with the result being something that probably resembled Marrakesh or Fez or other Moroccan cities. Instead, he sought out expertise from another culture but that expert found a way to bring new thinking to solve the problem while still adhering to some of the foundational elements of the native region. Cornut did not make Essaouira into just another French port city, but he also did not make it into just another Moroccan city.

This combination of the modern French design and the old Moroccan urban design appears in other cities in the area as well, though typically they are physically separate instead of being combined into the same location. For instance, the town of Fez has an old Fez, with its traditional medina, and a new Fez, with some of the sweeping boulevards reminiscent of what one would see in France today. The same is true for other cities, such as Marrakesh and Ouarzazate, though less so in the latter than the former. Indeed, the lesson of Morocco as a whole for the innovator is the power of combining the old and the new to create a completely new and innovative experience that is unique.

Always Have a Center

I have always been fascinated by the concept of a central courtyard in a home. It might have stemmed from visits to Roman ruins in my younger years in which I was struck by the appearance of a design element so different from what how we live today in the West, but at any rate I consider the interior courtyard to be the epitome of great design, with the ability of an architect to provide the inhabitant of a dwelling with a little taste of the outside world within the confines of his or her own habitation.

The inner courtyard is a staple of Moroccan constructions for residences, businesses, and religious structures. Stein writes that according to some historians, “the origins of the house with its central courtyard are to be found in the ancient Middle East.â€Â As mentioned above, one of the most amazing experiences in Morocco is to walk down a non-descript, narrow street, and pass through a door to see a magnificent, huge courtyard open up with natural light and elaborate decorations in the midst of the medina.

Stein states that the central courtyard reflects the notion of the “sacred center,†which is a key element in Islam. The Islamic religion is centered on the holy city of Mecca and Muslims anywhere in the world will point to Mecca when they pray several times each day. When they undertake the hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca), Muslims will walk around the kaaba in circles as part of their actions. As Stein notes, “[t]he first element of a residence to be designed is the patio or interior courtyard (wust ed-dar) [which is] the main area of the home [and i]t is from there that the other rooms radiate and it alone provides the source of light.â€Â In the courtyard itself, there will be a fountain in the center, with the design elements of the courtyard focused towards this central point to enhance its prominence. Colors, plants, and water will flow to and from this central locus, as a constant reminder of the sacred center.

Sacred Center – Note Octagon Shape

Sacred Center – Note Octagon Shape

Innovation Lesson – The lesson here for innovators is the importance of finding and acknowledging the sacred center of one’s work. It is easy to get bogged down in the day-to-day details of a work effort as one pursues tangents in search of true innovation, but one needs to maintain awareness of the overall objective at hand in a project. A center can be a mission statement or a vision provided to the team that allows everyone involved to stay focused on the overall goal of the work effort. The center can also provide a sense of balance as a measuring stick to determine how far one is straying from the original goal.

In other words, as one assesses new ideas or approaches to solving a problem, the innovator can measure those against the “center†of the project to ensure that the team does not stray too far from its intended work, no matter how promising any of those tangents may appear.

Sources:

Corinne Verner, The Villas & Riads of Morocco (New York: Abrams, 2005).

Achva Benzinberg Stein, Morocco: Courtyards and Gardens (New York: The Monacelli Press, 2007).

Julie V. Iovine, “Ancient Lessons in Modern Forms,†The Wall Street Journal (March 27, 2017), A12.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Essaouira

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodore_Cornut

Michael E. Porter and Mark R. Kramer, “Creating Shared Value,†Harvard Business Review (January-February 2011).

https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/353571-a-foolish-consistency-is-the-hobgoblin-of-little-minds-adored

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decumanus_Maximus

Author’s Discussion of Medina Complexity on Chad McAllister’s Everyday Innovator Podcast (https://theeverydayinnovator.com/133)

Wait! Before you go…

Choose how you want the latest innovation content delivered to you:

- Daily — RSS Feed — Email — Twitter — Facebook — Linkedin Today

- Weekly — Email Newsletter — Free Magazine — Linkedin Group

Scott Bowden is an independent innovation analyst. Scott previously worked for IBM Global Services and Independent Research and Information Services Corporation. Scott has Ph.D. in Government/International Relations from Georgetown University. Follow him on Twitter @sgbowden

Scott Bowden is an independent innovation analyst. Scott previously worked for IBM Global Services and Independent Research and Information Services Corporation. Scott has Ph.D. in Government/International Relations from Georgetown University. Follow him on Twitter @sgbowden

NEVER MISS ANOTHER NEWSLETTER!

LATEST BLOGS

The Evil Downside of Gift Cards

This past holiday season I saw probably one too many articles trumpeting the value of gift cards to retailers and how they are a great thing for retailers. My skeptic side starts coming out as I see article after article appear, and I have to start asking “Is the increasing prevalence of gift cards as a holiday gift (primarily Christmas) a good thing for retailers?”

Read MoreWhy the iPhone will not succeed – Yet

The new Apple iPhone is set to launch on June 29, 2007 and the press and investors are making it a darling. Investors have run Apple’s stock price up from about $85 per share before its announcement to $125 per share recently, but the iPhone still will not succeed – at least not yet.

Read More